Joe Meek - a Portrait Part 12: The tea chests - and what else remains

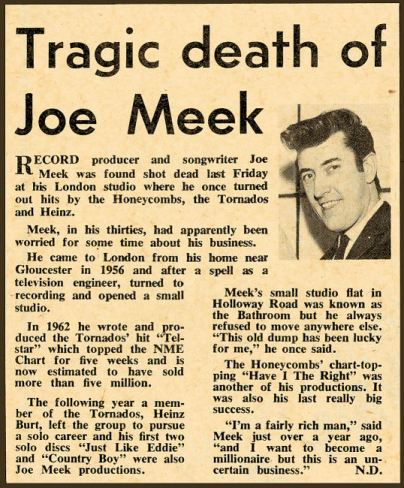

New Musical Express, February 1967

Joe Meek died at the age of only 37 years. Tornados' drummer Clem Cattini stated: "It was dreadful, but without wishing to sound morbid, I couldn’t see Joe dying any other way. He was never going to die a natural death. I don’t think his success brought him any happiness …" - Screaming Lord Sutch, who's career would have been different without Joe Meek, had this to say: "I was amazed as well as shocked and sad when I heard all this, as I had always thought of him as a fabulously successful producer, and it never occurred to me he had no money and only rented his flat. He was a great man and is much missed." Meek, who in the NME article shown above described himself as "fairly rich man", in fact left just under 300 Pounds in cash. In accordance to his will this money went to his heirs.

The tea chests And there are the so-called "tea chest tapes", sometimes named also "teachest" or "t-chest" tapes. Meek neither had an archive of his recorded tapes, be them master tapes, semi-finished recordings or demos, nor had he a special storage room for them. People who knew the studio at that time mentioned that in 304 Holloway Road at least five or six tape boxes were standing on every step, and whereever there was a little bit of space, even more tapes were piled up. Meek himself apparently had a good memory to delve through the chaos, but at some point even he lost the plot. At the time of Meek's death there were around 3000 tapes with circa 5000 recordings in the house. The estate administrator cased them into 67 tea chests and put these into a lumber-room. Meek's brother Eric and his brother-in-law took sixteen of these tea chests, five of those were given to an orphanage where the tapes were used as blank tapes. The remaining eleven chests were put into storage at the house of Meek's brother Arthur and were forgotten. Over the years the chests decayed, including their content. All in all around 1100 recordings went down irrecoverably this way. Fifty one tea chests were left at Holloway Road. For all intents and purposes, the estate administrator should have let erased all the tapes to sell them as blank tapes. But for some reason he didn't - maybe a premonition told him that later generations might have a different view on the value of this life's work than his own (and Meek's) contemporaries. So he sold the 51 chests including their content for 400 Pounds to Clifford Cooper, bass player of The Millionaires (they had been one of the last bands Meek ever recorded; their 45 Wishing Well was released in August 1966 and is one of these records nobody really can tell why they didn't take off). Cooper, who in 1968 founded the Orange amp factory, kept the tapes for decades and re-packaged them from time to time to prevent them from decay. That's why the tapes are still in good shape today, only the tea chests are gone. In September 2008 Cooper decided for age reasons that it would be time to hand the tapes down to somebody else. He commissioned an auction house to sell them. But the auction failed: In the end there were only seven bidders, and they missed the calling price by far. So the tapes are still at Cooper's now, and it's unclear what he plans to do with them.

The tea chest tapes

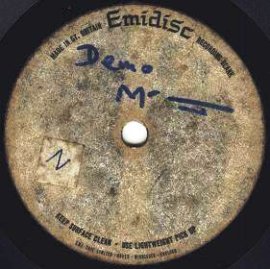

What's in the tea chests? Probably only one man could answer this question: Alan Blackburn, former chairman of the Joe Meek Society. He knows for sure because in the 1980s he listened to all the tapes and indexed them. According to him there are unreleased master tapes as well as snippets with studio conversation, a big number of demo songs by Dave Adams and Geoff Goddard, and several of Meek's own off-key composition singings. Besides this, as Blackburn says, there are mastered recordings of Mike Berry, Glenda Collins, Michael Cox, The Cryin' Shames, Heinz, The Honeycombs, John Leyton, The Outlaws, Screaming Lord Sutch and The Tornados - recordings that were obviously meant to be released. Further the tea chests allegedly contain demo recordings of (among others) Ray Davies, Georgie Fame, Jonathan King, Alvin Lee, Gene Vincent, Rod Stewart and the early Status Quo. The music gazettes and papers, however, especially highlighted two demos, one by David Bowie and his then band The Kon-Rads, and one by Tom Jones (short snippets of both can be heard here). The Tom Jones one is unmistakably authentic, and the sped-up voice indicates that indeed Meek did the recording. Probably also Bowie's voice is authentic, but in this case the recording doesn't show any of Meek's fingerprints, so there's no evidence that he did the recording. Last but not least it is said that there was also a demo tape of a certain Mark Feld. This guy was 16 at that time (1963) and later got famous under the name Marc Bolan with his band T. Rex. An acetate copy of this weird sounding demo named Mrs. Jones has been circulating on the web as MP3 file for a while. But is it really Marc Bolan singing? The time would be right, but that's all we know. The acetate shown below is from the collection of Dave Adams, but even he doesn't know for sure who's to be heard on it. As the (now closed) website meeksville.com stated some years ago rather meandering, allegedly some (unfortunately unnamed) "long-term friends and relatives" of Bolan's "saw themselves in the position" to "believe almost surely" that this actually is his voice. In plain language that means: We don't know. The "Record Collector" (November 2008) on the one hand ascribed the recording to Bolan, but on the other hand in the same paragraph the author states that there are doubts in its authenticity. In plain language that means again: We don't know. But one thing we know for sure is that Meek used to edit his singer's voices by equalizer and/or by varying the recording speed. It doesn't help: As long as nobody comes up with a solid evidence, doubts remain justified.

Acetate "Mrs. Jones" Only Cliff Cooper and/or Alan Blackburn could bring clarity to this and other questions. They could publish photos of the tapes or tape boxes with Meek's handwritten inscriptions, authentifications by the respective artists or other appropriate documents. As long as this doesn't happen, all statements or claims should be taken with a pinch of salt.

Several thousand recordings? Some press articles stated that there are "several thousand" recordings of proper sound quality in the tea chests. But Joe Meek didn't work for more than seven years as independent producer in his own studio - 2500 days. He actually produced circa 700 tracks during this time, sold them to record companies and did promotion work. Seen in this light it has to be asked seriously: How could he been able to do such an enormous number of recordings? That's not going to work out, even if all the tapes were simply demo recordings. No way. Moreover, according to Blackburn, the inscriptions on the tapes are partly ambiguous, unreadable or encrypted in a way that hasn't been decoded yet. Nobody knows for sure, but it may be allowed then to assume that most of the tea chest tapes are demos that were sent to Meek by bands, managers and artist's agencies. Some of them may be interesting, but they wouldn't be Meek recordings then.

Stereo mixes and extended versions? Furthermore, Alan Blackburn says he found "extended versions" and "stereo mixes" in the tea chests. What is to think about that? Meek released nearly all of his recordings in mono. As described in chapter 3, this was not a dogma, but he saw himself in the first place as producer of 45s, and they were monophonic at Meek's lifetime. Meek's multiplay recording method leads to a couple of intermediate stages until the recording is finished. Played on a two-track stereo tape machine, these these intermediate stages indeed have a sort of stereo effect. Their fingerprint is the "hard" channel separation: One track usually has the instrumental backing, the other has an added solo instrument or the vocals. A couple of recordings like these have been released on some Meek CDs, but not one of them is convincing. No wonder, because - as said - the recordings are intermediate stages and not made to be released this way. But what we know for sure is that Meek kept a lot of these tapes. From time to time he came back to them to make new backing tapes from it, or he integrated new singers into old backings. With the utmost probability these intermediate stages are the secret behind the reputed "stereo mixes", and they also would explain the enormous number of allegedly existing recordings with proper sound quality. And the "extended versions"? They may be simply a misinterpretation. In all probability it's just the other way round: Meek recorded many of his tunes "too long" and had to cut them down afterwards to an acceptable length for a 45 release. Anyway, there is a number of recordings that can be attributed to Meek for sure - how many ever it may be. Blackburn estimates that there's enough material for at least ten CDs. That wouldn't be "thousands" of recordings then, but something between two and three hundred. Which probably is more or less the real number of usable recordings.

What else remains The British Music Producers Guild (MPG) named an annual innovation award after Joe Meek ("Joe Meek Award for Innovation in Production"); the first awardee in 2009 was musician and producer Brian Eno, the 2010 award went posthumously to Les Paul. Two biographies have been written about Meek, several radio documentaries were broadcasted, there are two documentary films. In 2005, Meek's life was transformed into a stage play named "Telstar". A feature film was finished in 2007 under the same title, received its festival premiere in 2008 and finally had its theatrical and DVD release in 2009 after some argy-bargy about legal questions; in 2012 it was also shown on TV. The movie is a biopic, it was not intended to be a documentary anyways, and even it's well made technically, it doesn't help: As a feature film it's not completely convincing. Already in early 2010 the DVD could be found in the bargain bins of several online stores.

Queer music? Nearly anyone who had to deal with Joe Meek knew he was gay, many of these people were gay themselves. Without any question the daily life as a homosexual was hard at that time. In England, homosexuality was a violation of law until 1967 and criminally prosecuted. Blackmailing was a daily occurrence. While in New York City at least a rudimentary sort of homosexual scene was developing at that time (comparable maybe to the arising Berlin scene in the 1920s), gays and lesbians in England, in light of the law and the restrictive police operations, had no other choice than to remain publicly invisible. As musician Tom Robinson stated in the Joe Meek Society guest book: "Most gay and bisexual men pre-1967 had every reason to be fearful and paranoid." Only within the limits of some closed circles - like the music or the arts scene - there was a kind of gay "sub-sub culture" existing. Within these scenes people knew each other. In the everyday life there was nothing more than some smalltalk figures of speech and a couple of dress codes that made it possible for gays and lesbians to recognize each other. That was all there was. Meek, at least, was (relatively) lucky enough not to be forced to hide his homosexuality completely within the circle he worked in, besides this he was his own boss. In 2007, the German edition of the "Rolling Stone" made the case that Meek produced "gay music". This is simply a bit exaggerated. Several writers, filmmakers, journalists and also fans took great pains already to find "gay lyrics" or even a "coming out" song in Meeks oeuvre. The song Hobbies, produced with Jenny Moss in 1963, has been mentioned several times as an example because the lyrics are talking about "boys, boys, nothing but boys". But there's the rub that Meek didn't write this song, and besides this, the singer is female - no "coming out" far and wide. Even songs that were actually written by Meek don't give any clues in this direction. Sometimes some of Meek's productions have autobiographical hints, fears and dreams. Listening to Loneliness (with singer Mike Berry, December 1962) one has to be deaf not to realize who's talked about in the lyrics. There are some more examples of this kind - Please Let It Happen To Me with singer Jenny Moss, December 1963, Poor Joe recorded with Carter-Lewis & The Southerners in 1962, Not Sleeping Too Well Lately, produced in 1965 with The Honeycombs, and some more. But in all of these songs there's not the slightest connection to the sexual orientation of their lyricist. Meek's lyrics, as long as they don't deal with the Grim Reaper or extra-terrestrial visitors, never leave the level of everyday pop songs. There's only one production in which Meek is clearly showing his colors: The Tornados' flip side Do You Come Here Often?, released in August 1966. It's a corny organ shuffle number which in its center section includes some small talk of two men in a bar. But this "smalltalk" is not as harmless as it seems to be: In a clever arrangement this dialogue lines up several "code phrases" as they were mentioned above. For sure everyone in the gay scene knew immediately what these two guys were talking about, for everyone else probably the whole thing didn't make any sense. What was the reason for Meek to produce this record? Was it really meant to be a public statement? Or did he simply let off some steam after all the stress he had in the months before? Today this question cannot be answered seriously anymore. Only one thing can be said for sure: In the UK of the 1960s it would have been impossible for Meek to express himself more clearly than he did here - he had to fly underneath the official radar, otherwise he would have invited even more trouble than he had already.

Potential hit bands, The Beatles and the amphetamine More than once Joe Meek showed potential hit bands the door. The example Dave Dee, Dozy, Beaky, Mick & Tich has been mentioned before, and as far as we know, Meek also rejected The Beatles. By stressing this point again and again and mentioning it in biographies and blog entries, it's probably intended to demonstrate Meek's confused state of mind or to display him as a sort of moronic unicum. But there's no reason for that. Decisions of this kind are nothing special. Misjudgments were and are a daily occurrence in every record company or publishing house. The reason is plain simple: Nobody, neither producers nor A&R people, has other standards than his own subjective feeling. There is no recipe to cook a hit. Even the legendary producer Sam Phillips who really was a gifted talent scout had no real clue what to do with the talents of Roy Orbison or Johnny Cash, and so their Sun recordings are not really convincing. And when Meek rejected the Beatles, we should remember that in the light of the demo tapes Brian Epstein played to him, he by far wasn't the only one rejecting them. In fact, The Beatles had been rejected where ever he had asked; probably Meek was more or less Epstein's final try. (Five of these demo tracks can be heard on the Beatles' "Anthology" CDs.) Even Bert Kaempfert, who had produced their first recordings for Polydor in Hamburg, stated: "It was obvious that they were enormously talented, but nobody, not even themselves, knew what to do with it and where they were possibly heading" - and so he had let them go. The experienced Decca A&R man Dick Rowe rejected the Beatles too (at least he signed the Rolling Stones to the company later). Even George Martin waited several months until he invited the band for an audition, and the Beatles (who at that time were known mainly as a cover band) didn't pique his interest until they played a couple of their own compositions to him - obviously that gave him a flash of intuition that this might be their real talent. Sometimes - usually a bit tongue-in-cheek - there's the saying that if there had been a collaboration between Meek and the Beatles, then the "Sgt. Pepper" album would have been recorded already in 1964. A nice bon mot, but let's face it: A collaboration between an authoritarian stubborn guy like Meek and highly self-confident musicians and songwriters like Lennon/McCartney would have failed within weeks. Meek, it's true, made heavy marketing mistakes, ignored upcoming trends or recognized them not before it was too late. Instead of this, he more and more desperately tried to come up with a second Telstar - without success, of course. Moreover, there are a couple of potential hit recordings which ended up on flip sides or, for what reasons ever, weren't released anyway. Wrong decisions of this kind, as said, are nothing rare in the media industry, but with Meek they increased in 1965 and 1966. Unquestionable a sign that more and more he lost the plot. But whatever appears in the press or the blogosphere from time to time: There is no reason to ascribe Meek's slipping attention to schizophrenia, undiscovered bipolar disorder or "mental illness" whatsoever. Today, more than 45 years later, there would be no way to bring up a proof for that anyway. Meek's long lasting abuse of uppers and downers in combination with his life-long irascibility and suspiciousness is enough to explain his mental condition. As mentioned earlier, the abuse of amphetamine was downright a fad in the 1960s. Every doctor knew the consequences under the name "amphetamine psychosis", and Meek's symptoms are textbook examples for this. One thing remains to be asked: In view of Meek's increasingly disturbed state of mind and behavior, why did no friend and no collaborator see that this man wasn't able to find the way out anymore from his own strength?

Sources see chapter 13 [Home] [Complete Recordings] [Triumph Story] [CD Discography] [Noten/Scores] [Telstar Cover Versions] [Meek in Germany] [Literature, Documentaries etc.] [Miscellaneous] [Contact] © 2006 Jan Reetze last update: March 25, 2014

|