|

Joe Meek - a Portrait Part 2: Triumph Records, RGM Sound Ltd., 304 Holloway Road, Meeksville Sound Ltd.

It's A Triumph! Joe Meek had a quality that was rather unwelcome in recording studios at that time: He had own ideas. That was scandalous. At that time, sound engineers were figures in white coats who did what the music producers told them to do, and besides this they had to keep their mouth shut. But Meek didn't do that, and so he soon had many quarrels with nearly everyone. Finally the Lansdowne studio gave him the boot. Because of this, but also to spare himself from going back to door-to-door salesmanship, Meek decided in early 1960 to use the money he had earned with his composition Put A Ring On Her Finger to start his own record company. In the U.S. this would have been nothing special anymore (around 1960 there were circa 1500 independent record labels working in the U.S., in the mid-sixties the number had doubled), but in the UK, independent labels were unusual at that time; there were hardly a handful of them (probably the best known were Oriole and Ember Records). Often (for a long time even here on this page) it has been said that by doing this Meek became "Europe's first independent record producer", but this cannot be maintained. In fact this honour is due to the aforementioned jazz producer Denis Preston (1916 - 1979): He was not an employee of a record company, he worked with jazz bands and produced music with them on his own risk and account. Preston also was the first independent producer in Europe who founded his own recording studio (the mentioned Lansdowne Studio), and moreover, he established a record label of the same name. Preston didn't invent this method, it had been common practice in the U.S. for years, and he knew it from there. Meek had learned about the idea of independent producing during his time at Lansdowne, and now he adopted it for himself. The result was Triumph Records.

Triumph sleeve But the whole affair turned out to be anything but a triumph. There were two main reasons for the failure: First, Meek simply spent too much money for productions. The second reason was Triumph's partner company, Saga Records. This company was supposed to do the distribution of the Triumph output, but as Saga specialized in film music and budget productions of classical music, it was not able to place Meek's pop music productions appropriately in the retail shops. (There were more reasons for the flop, but at this point these information should do. However, the Triumph Records Story has its own chapter; if you want to know all about it, please go here!) In the end, Triumph Records released no less than eleven 45s produced by Meek; they all had the prefix "RGM" (his initials: Robert George Meek) at the beginning of the catalogue number. Ten of them turned out to be more or less flops, and when finally in summer of 1960 the eleventh one took off (Angela Jones with singer Michael Cox), Meek had already left the company.

RGM Sound Ltd. After leaving Triumph, Meek did the obvious: He continued producing recordings with his artists, and had no choice but to return to selling his tapes door-to-door to record companies. The idea of producing recordings independently and licensing them to an established record company for exploitation looks quite convincing. But there's one big catch: The producer has to let go the control over the tune. Once he has licensed the recording to a record company, he has no impact anymore on what the company does and which way the record is marketed. Besides this, one has to know that at that time independent producers were anything but welcomed by the established companies. The record companies had their own in-house producers as well as A&R departments, and usually they saw no reason to accept help from outside the company. So this kind of business only worked by socializing - and these personal contacts had first to be built up. Wilfred Alonzo "Major" Banks, 1961 Now, after Meek had some successes, Saga board member Wilfred Alonzo "Major" Banks jumped on the train. He, who once had handed the Triumph project to a colleague, smelled money now. He offered Meek a joint music production company, paid him a weekly salary of 20 Pounds as long as the company didn't make profits, and financed a self-owned sound recording studio. There Meek would be able to work without time limits. The company was named "R.G.M. Sound Limited" and officially registered on September 12, 1960.

RGM letterhead

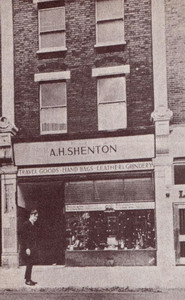

304 Holloway Road Joe Meek sought studio space near the Saga offices, and he found it in the three empty floors above a leather goods shop at 304 Holloway Road - a four-lane arterial road in Islington, probably one of the most sombre places the north of London had to offer. One had to be Meek to jump on the idea of setting up a sound recording studio in these tiny narrow rooms that, in fact, simply were an apartment. And moreover, the street in front of the windows was extremely noisy. With the help of musician Dave Adams (more info on him here), who was a skilled carpenter, Meek developed two rooms on the second of the three floors into a studio, where working and living areas more or less merged. Meek lived and worked here until his death.

304 Holloway Road, Joe Meek at the entrance Using his A&R contacts from several record companies, keping in mind the Triumph experiences in mind and endowed with the Angela Jones success, his new company and the distribution went much better than before. Soon that top-flight labels like HMV (His Master's Voice), Parlophone, Decca and Pye were among his customers. Most of his records now stated "An RGM Sound Production" (since 1964 "Meeksville Sound Production") on the label. And the price of his productions was anything but cheap. The contract between Meek and the "Major" stated that all revenues were to be shared fifty-fifty between them - including, as Banks insisted in, the royalties Meek would receive for his compositions. Meek, however, was not willing to share his royalties (correctly so, seen from the copyright laws), so he went on writing under his earlier pseudonym Robert Duke. But it didn't take long until Banks became aware who, in fact, this "Robert Duke" was. In 1962 finally, after a row between the two of them, this article was deleted. All royalties remained with Meek from then on, and from this moment he more or less stopped using pseudonyms. (More information about Meek's compositions and pseudonyms can be found here.) Banks controlled nearly everything and sometimes became a real torment. Not because he saw Meek as his opponent (on the contrary, he admired Meek's skills), he simply was a good businessman who had already seen at the times of Triumph what happened if someone gave Meek free access to the cheque books. Meek was completely clueless and uninterested about the administrative side of the company. He always felt that the "Major" deceived him. In fact is was he who thought up several backstairs methods to cheat Banks of his profit shares. And Meek usually left the distasteful jobs to Banks, but he reacted hypersensitive when the Major wanted him something to do. On the other hand the two of them developed a couple of really clever ideas. One of them: Most compositions written by Meek were published by the music publishing house Campbell Connelly & Co Ltd. Meek and Banks talked them into starting a subsidiary company and brought Radio Luxembourg into joining the company with with a share of 50 per cent. This company was named Ivy Music Ltd, and it published most of Meek's compositions from then on. The idea behind this construction was: For every record they aired, Radio Luxembourg had to pay royalties which in part went to the music publishing house. But when Radio Luxembourg played a composition published by Ivy Music, a part of the royalties came back to the station's own cash register. Meek had no problems after that to talk the Radio Luxembourg people into playing his compositions. But the troubles between Meek and Banks went on, more or less because of Meek's permanent mistrust. In 1964, with the royalties from the hit Have I The Right, Meek bought out his business partner with 14,000 Pounds. To give a clue what this amount meant: Today this would be equivalent to circa 450,000 Pounds, nearly 500,000 Euros or 730,000 US Dollars. The amount shows clearly that RGM Sound Ltd. was a high-profit two-man hit machine up to this moment. The decision to kick out Banks didn't turn out very lucky; more on this in chapter 8.

Meeksville Sound Ltd. To be on the safe side and to prevent Banks from any potential additional demands, Meek shut down the company completely and founded a new one: "Meeksville Sound Ltd." (probably a friendly hint to the Motown label and their slogan "Hitsville, U.S.A."). His new co-partner in this company was show business entrepreneur Thomas "Tom" Shanks. His participation in Meeksville was only 1 per cent; in the first place Meek wanted to use Shanks' business connections. Shanks had good connections indeed. He managed several companies, among them Petula Clark Ltd. This singer, best known for her hits Downtown (1964) and Don't Sleep In The Subway (1967), was the first artist in Great Britain who had set up her own marketing company. It is well possible that Meek got ivolved with Shanks only for the reason to sign this higly successful Petula for Meeksville. But it didn't happen.

Meeksville letterhead

Sources see part 13 [Home] [Complete Recordings] [Meek Compositions] [Goddard Compositions] [Triumph Story] [CD Discography] [Noten/Scores] [Telstar Cover Versions] [Meek in Germany] [Literature, Documentaries etc.] [Miscellaneous] [Contact] © 2006 Jan Reetze last update: May 1, 2013

|